What do you get when you cross enka with jazz, R&B, gospel, and rock ‘n’ roll? Wait – what exactly is enka, you ask? Enka is a sentimental Japanese ballad whose melodramatic, gushing lyrics tell tales of lost love set against a backdrop of the type of sweeping music you’d hear in an elevator. Still don’t know? Maybe this will help. Here’s a sample of the classic enka tune “Tsugarukaikyo-Fuyugeshiki” (“Tsugaru Strait – Winter Scenery”) performed by famed enka singer Sayuri Ishikawa.

Back to the original question. What do you get when you cross the sound from the video above with jazz, R&B, gospel, and rock ‘n’ roll?

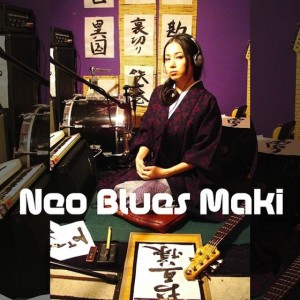

The answer is Neo Blues Maki, a five-member band based in New York that melds several musical genres with these sentimental Japanese ballads. Why enka? Before we look at why, let’s talk about who they are.

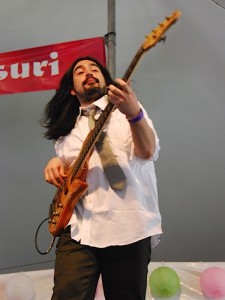

Neo Blues Maki is the brainchild of bass player Soshi Uchida, a native of Fukuoka. After attending Berklee College of Music in Boston, Uchida returned to Japan, immersing himself in the Tokyo music scene. He performed for a variety of singers and musicians and was the leader of the jazz/funk band Grooveline, which garnered a major recording deal in Japan.

Uchida was incredibly busy with different projects, but he eventually began to lose interest.

“The sad thing was, I wasn’t excited about any of it,” Uchida says of being a working musician in Tokyo. “The experience of performing lacked inspiration . . . I knew deep down inside I had a lot more growing to do.”

Uchida decided he could grow in New York, and in late 2006 he came here without a firm plan, other than to get a gig. It’s a leap of faith that can be intimidating for anyone, especially for Uchida, a self-described “typical reserved Japanese guy.”

“I’m not that aggressive,” Uchida admits, but he found the intestinal fortitude to attend Open Mic Night at the Village Underground every Sunday and Monday for almost a year, playing bass onstage. Through that experience Uchida met a number of talented musicians, but it was two friends he knew from Japan who helped shaped his ultimate project, Neo Blues Maki.

One friend is Kayo Yoshioka, a singer whose main goal in coming to New York was to learn gospel music. (Gospel is a hugely popular genre among Japanese people, although they tend to overlook the religious aspect of the songs.) The other is Junya Yamaguchi (aka “Junior”), a talented keyboard player and arranger with expertise in jazz fusion, funk, R&B, as well as gospel.

When the trio came together, they decided they needed something interesting and unique to pursue. Which brings us back to the question of why enka?

Yoshioka was passionate about singing in English. However, Uchida thought they could create something special. Their sound, Uchida stressed, had to have substance.

“I felt like there was something [among the trio’s roots] that had a lot of potential to entertain people in New York,” says Uchida, who didn’t want that potential to be “something where Japanese people were admiring Western music too much.” Nor did he want their music to be a version of J-pop.

“Even though Japanese culture is so popular today [in the US], it’s only the anime aspect or the Harajuku aspect, but it’s none of this traditional, soulful aspect,” says Uchida.

Uchida somehow found himself watching enka videos online while researching different genres. Enka wasn’t something Uchida listened to on a regular basis, but something clicked when he watched those videos. “It re-emphasized that these enka singers are no joke,” says Uchida.

Yoshioka is no joke either, and Uchida knew her voice could handle the soul, emotion, and expression that singing enka requires. As it turned out, Yoshioka already knew the lyrics to many enka songs by heart, having been exposed to the genre when she was young.

“Even though she hasn’t really actively been singing enka, it’s in our blood,” says Uchida. “You grow up watching the New Year’s TV show [Kohaku Uta Gassen]. Your grandfather, grandmother, your father, your mother – enka is in almost every Japanese citizen’s ear.”

Hence Yoshioka became the symbol of Japanese tradition for the band, carrying what Uchida describes as the group’s most crucial role. For performances, she dons a kimono as enka convention dictates and belts out ballads in her native Japanese.

Knowing most New York audiences weren’t going to understand the lyrics, Uchida had to come up with something that would transcend the language barrier. While they were excited that the focus of the band would be on enka vocals, Uchida and Yamaguchi weren’t particularly psyched about playing enka music.

“We were in New York being exposed to so much inspiration from the New York music scene: Gospel, R&B, jazz, hip-hop, rock, even the pop music,” says Uchida. “Everything is just so inspiring that we wanted to sort of try to make all of that mesh.”

Thus, Neo Blues Maki – the hybrid of “soulful enka with progressive fusion/rock/jazz arrangements” – was born.

Finding the other musicians to fill out the rest of the band was easy for Uchida and Yamaguchi, as their gigging and open mic night appearances had exposed them to a goldmine of local talent. They were looking for competent musicians who had the “right mindset so that we can achieve these somewhat crazy musical approaches with the least amount of nonsense,” says Uchida.

So they enlisted the services of guitarist David Linaburg, who fit the bill because of his wide range of styles from rock, blues, jazz, R&B, gospel, and hip-hop. Needing a drummer with superb technique, Uchida turned to Lucianna Padmore, a native New Yorker who accompanied Uchida on an R&B gig in Morocco. Of Padmore, Uchida says, “She brings the quality of Neo Blues Maki’s performance to another level.”

With the band members in place, Neo Blues Maki started doing covers to test the format, working with classic enka songs “to see if we were capable of re-inventing them with this new concept,” says Uchida. Once everyone felt comfortable, they worked on their own material. The result is three original songs that comprise Neo Blues Maki’s first CD, a self-produced venture that was released in April 2011.

How do the non-Japanese members of Neo Blues Maki tackle this foreign concept? Without realizing it, Padmore had heard enka from other Japanese friends, so she was familiar with that facet. She says communication between band members is the key to working through the difficult musical arrangements. She also admits that there are times when she and Linaburg need to ask what Yoshioka is singing.

“We’ll be playing and smiling, but she’s talking about someone getting killed,” Padmore says with a laugh.

Padmore also had a tough time describing the band to her father. “You just have to hear it,” she told him. When he did, he loved the sound and the emotion of Yoshioka’s voice, despite not understanding anything she said.

“If you don’t know the language, you can still hear the story, you can tell something is going on,” Padmore explains. “It’s like with opera. You may not know a word of Italian, but you’re there, going up and down with [the singers].”

Although the enka hybrid is Uchida’s pet project, each member of Neo Blues Maki finds the time to perform with other musicians. Uchida’s credits include Les Nubians, Brian Slade (aka Tonex), Sandra Bernhard, the Delfonics, and even Maranatha Baptist Church. Yoshioka continues to pursue gospel music, and Yamaguchi has played for singer/songwriter Toni Menage, YahZarah, and the NYC Interdenominational Gospel Choir. Linaburg appears on the latest album by J. Cole, the 24-year-old rapper who was recently nominated for the Best New Artist Grammy. Padmore’s activities include a Frank Zappa-inspired, wide-open rock ‘n’ roll band as well as a tour with Grammy-nominated jazz guitarist Ronny Jordan.

Uchida encourages these outside projects because he believes they make the overall sound of Neo Blues Maki stronger. They can go one or two months without rehearsing, but once they’re in their rented studio space in Queens, the mesh is instant.

Padmore enjoys returning to Neo Blues Maki for the rapport as well as the complicated arrangements. “We’re always progressing,” the drummer says, saying it’s almost a spiritual experience when the band reunites after a long hiatus.

So where and when can you find Neo Blues Maki?

Although Neo Blues Maki has appeared at Japanese-related events such as Sakura Matsuri, j-Summit NY, and Japan Arts Matsuri, Uchida wants to be included in shows that don’t call for a Japanese element. “I feel like that in a sense would make the Japanese aspect even more noticeable,” says Uchida.

Uchida is considering applying for permits to perform outdoors to introduce more people to their unique sound. “I have confidence in the concept that we bring to the table,” says Uchida. “Just like going to the Village Underground moved my life in New York forward, put yourself out there, and random people will show up.”

But that’s in the future. For now, their three-song CD is available for purchase on iTunes, and the band will make a repeat performance at Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s Sakura Matsuri on Saturday, April 28.

Neo Blues Maki will also continue to fulfill Uchida’s vision of providing unique Japanese-inspired entertainment to New Yorkers. “The inspiration from the New York music scene is a tremendous part of what I do when I try to arrange music,” says Uchida. “None of this was possible for me in Japan.”

So when you cross enka with jazz, R&B, gospel, and rock ‘n’ roll, you get Neo Blues Maki, a band that might be hard to describe but easy to like.

Leave a Reply