Article by Christopher Bourne

Photo credit Niko

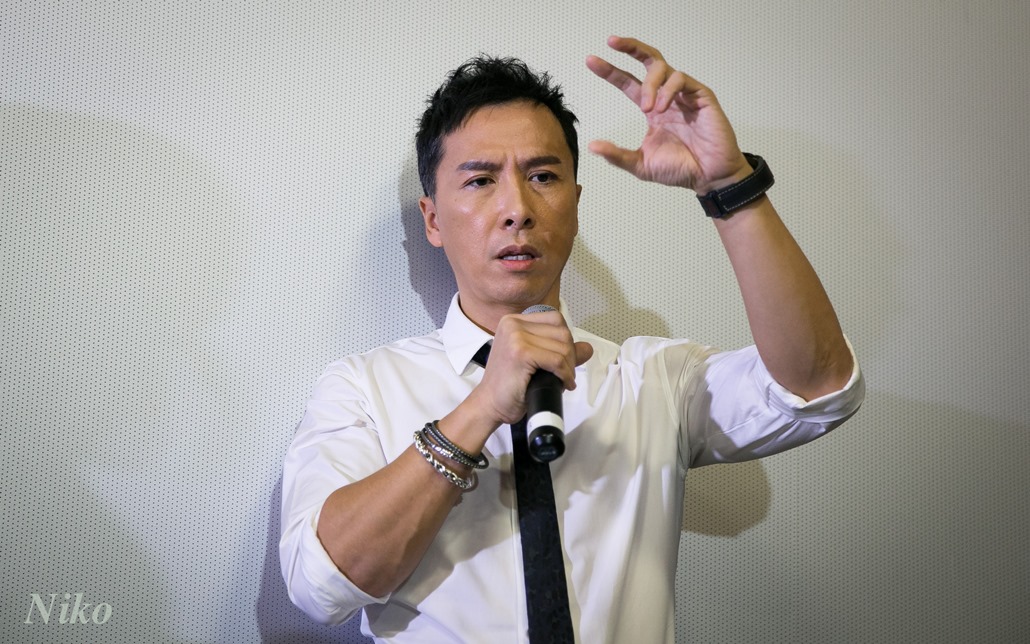

On November 7, 2013, martial arts film megastar Donnie Yen participated in a Q&A at the AMC Empire on the final day of the New York Chinese Film Festival. The Q&A session occurred in between a double feature screening of two of his films: the 2008 feature “Ip Man,” and his latest film “Special ID.” During the Q&A, Mr. Yen reflected on what an influential breakthrough “Ip Man” was, both for the martial arts film world in general, and for him personally. “I always try to look for another Ip Man,” Yen said. “What I mean by that is I try to strive for another character that can equally reach out and touch all of you as Ip Man did.” Yen chose to show both of these films together at the festival to show the range and contrasts in his action film acting, from the period Wing Chun style of “Ip Man” to the contemporary MMA fighting featured in “Special ID.” Yen also remarked later in the Q&A session that he always strives to convey a positive message in his films: “I believe every one of us has this quality of being a superhero, that power you can share with others, to do good things.” This message especially comes through loud and clear in “Ip Man,” which remains one of the best, if not the very best, films of his still evolving career.

The very reverential and patriotic “Ip Man,” Wilson Yip’s biopic about the titular martial arts master best known for having Bruce Lee as his most famous disciple, is a pleasing throwback to classic kung-fu films which features an engaging lead performance by Donnie Yen as Ip Man. The first film in a projected trilogy on Ip Man’s life, “Ip Man” begins in 1935 in Foshan, a city in China’s Guangdong province renowned for its superior brand of martial arts. Ip, revered by all the masters of the martial arts schools in Foshan as the foremost practitioner of the Wing Chun fighting style, does not run a school or take on students. However, Ip’s spacious mansion has become a de facto university training course for those who want to test their skills against the master. One of these is Liao (Chen Zhihui), a local martial arts schoolmaster, who challenges Ip to a duel while he is having dinner with his family. This is not an unusual circumstance, as evidenced by the exasperated glances thrown Ip’s way by his wife Yong Cheng (Lynn Hung), increasingly weary of these interruptions and resentful of Ip’s inattention to their son. The unfailingly polite and courteous Ip invites Liao to sit and eat with them, after which Ip defeats him with ease, telling Liao, “Thank you for being lenient.” Ip always fights his challengers behind closed doors, promising silence to protect their reputation. Unfortunately for Liao, someone eavesdrops on the fight and spreads the story of Liao’s defeat all over town, causing an angry Liao to confront his accuser the next day at a teahouse where Ip is having lunch. This leads to a brawl that local inspector Li Zhao (Lam Ka-tung) has to break up. Li is contemptuous of these martial arts fighters, declaring that they are behind the times, and that guns are the proper weapons for fighting. Ip coolly refutes this notion by taking hold of a gun Li has pointed in his face, and popping out the cylinder with a swift motion. These early scenes of the film establish Ip as a calm, Confucius-like healer of conflict, a paragon of wisdom.

Later, Zhao (Fan Siu-wong), a martial artist from the north, breezes into town, beating up all the masters in town and plotting with his boys to take over, declaring that no one in Foshan really knows martial arts and the place is full of nothing but pushovers. Zhao makes his way to Ip’s residence, where his wife reluctantly agrees to let him fight, with one proviso: “Don’t break my things.” Zhao gets off some verbal digs against Ip’s use of the Wing Chun style, and the fact that it was created by a woman. In a great scene full of humor – Ip’s young son rides his tricycle through the scene at one point to remind Ip of his wife’s warning – Ip dispatches Zhao as coolly as all the rest, finishing him off with, of all things, a feather duster.

However, an event soon follows which even Ip Man can’t prevent – the 1937 Japanese invasion of China, which decimates and impoverishes much of the population of Foshan. Ip, having lost his house to the Japanese army, begins working in a coal mine, where many of his fellow martial artists are also employed. Miura (Hiroyuki Ikeuchi), a Japanese general who, conveniently for the film’s plot, also practices martial arts, soon arrives in town, sending his henchmen to the coal mine to look for Chinese who will fight in an arena he has set up, with bags of rice offered as a reward. When one of Ip’s friends is killed by the general during one of the fights, Ip angrily goes to the arena, where he defeats ten fighters at once, proudly refusing to take the promised rice. The intrigued general tells Ip to return to the arena. When Ip fails to do so, one of Miura’s henchmen seek Ip out, arriving at Ip’s house, where he beats up some Japanese soldiers after they threaten his family, making it necessary for Ip and his family to go into hiding. After sending his wife and son away to safety, Ip seeks out Miura, who wants Ip to teach him Chinese martial arts. Ip refuses, saying, “You Japanese don’t deserve to learn martial arts.” He challenges Miura to a one-on-one fight, setting up the film’s final showdown.

These details, and the broad sketches of Ip’s early life shown here, of course, serve mostly as a frame for the acrobatic fight scenes, of which “Ip Man” offers plenty. Donnie Yen, no surprise, handles these scenes with the grace and aplomb with which he is renowned. What may be a surprise, however, is how good he is in the scenes which don’t involve fighting; he plays Ip Man with an understated appeal which nicely renders the humility and humanity of this character. An even better performance is given by Lam Ka-tung – who will be familiar to fans of Johnnie To’s films – as Inspector Li, who later becomes an interpreter for the Japanese army. His character is pretty much the only one in the film allowed any shades of complexity, a man who sees his own actions, which others would call traitorous, as simply a means to survive. Lam does a great job in effectively making his character’s internal conflicts sympathetic. The ever-ubiquitous Simon Yam, as the owner of a local cotton mill, also impresses in his brief scenes.

Wilson Yip is the consummate craftsman, the widescreen framing and period details (with Shanghai standing in for 1930’s Foshan) lending the film a pleasingly retro feel, highlighting Kenneth Mok’s impressive production design. The script by Edmond Wong is fairly basic, and rather simplistic in terms of character – in short, Chinese good, Japanese bad – but this is arguably well in keeping with the other consciously old-fashioned elements of the film.

Leave a Reply